Full description not available

A**.

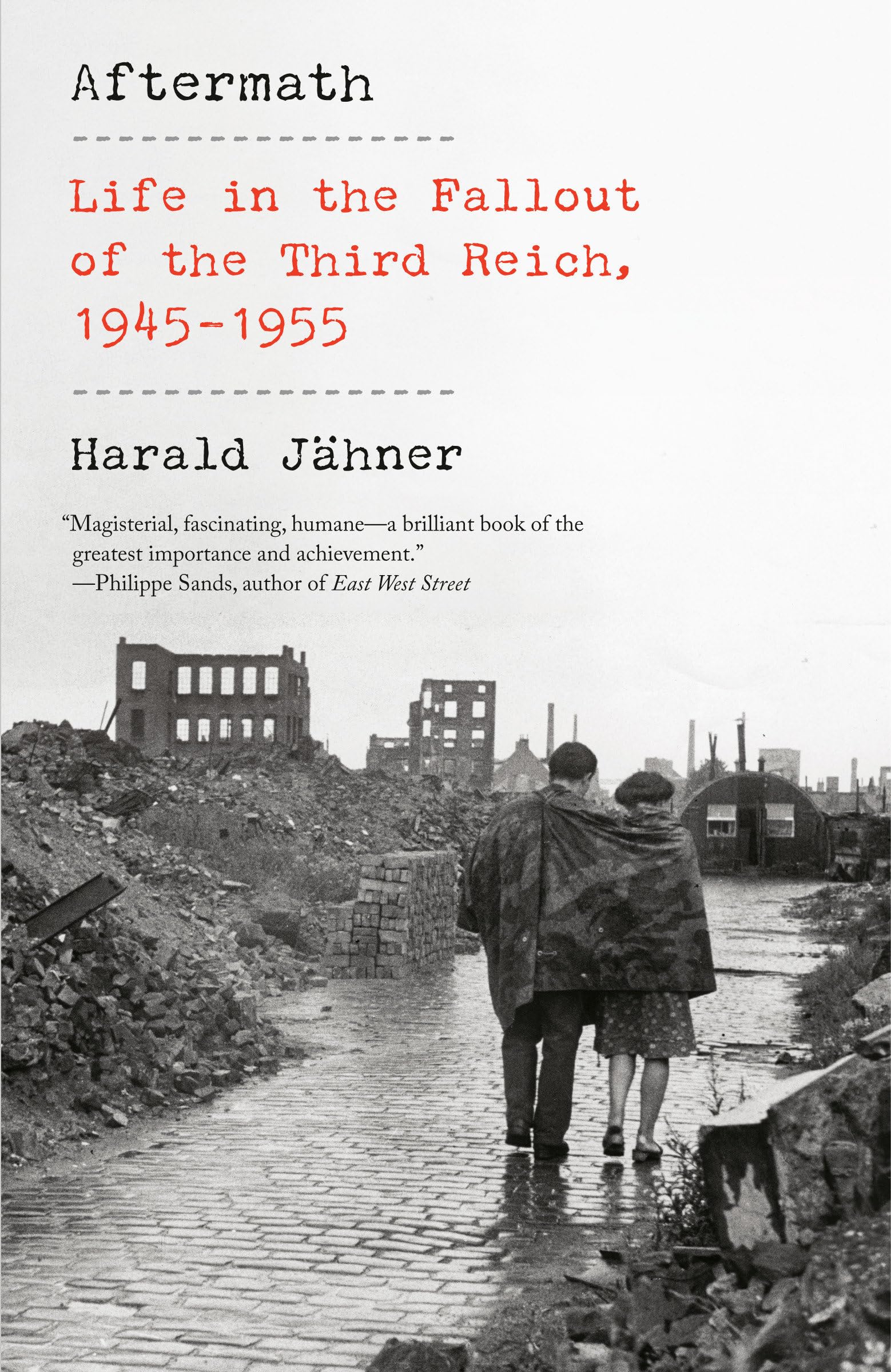

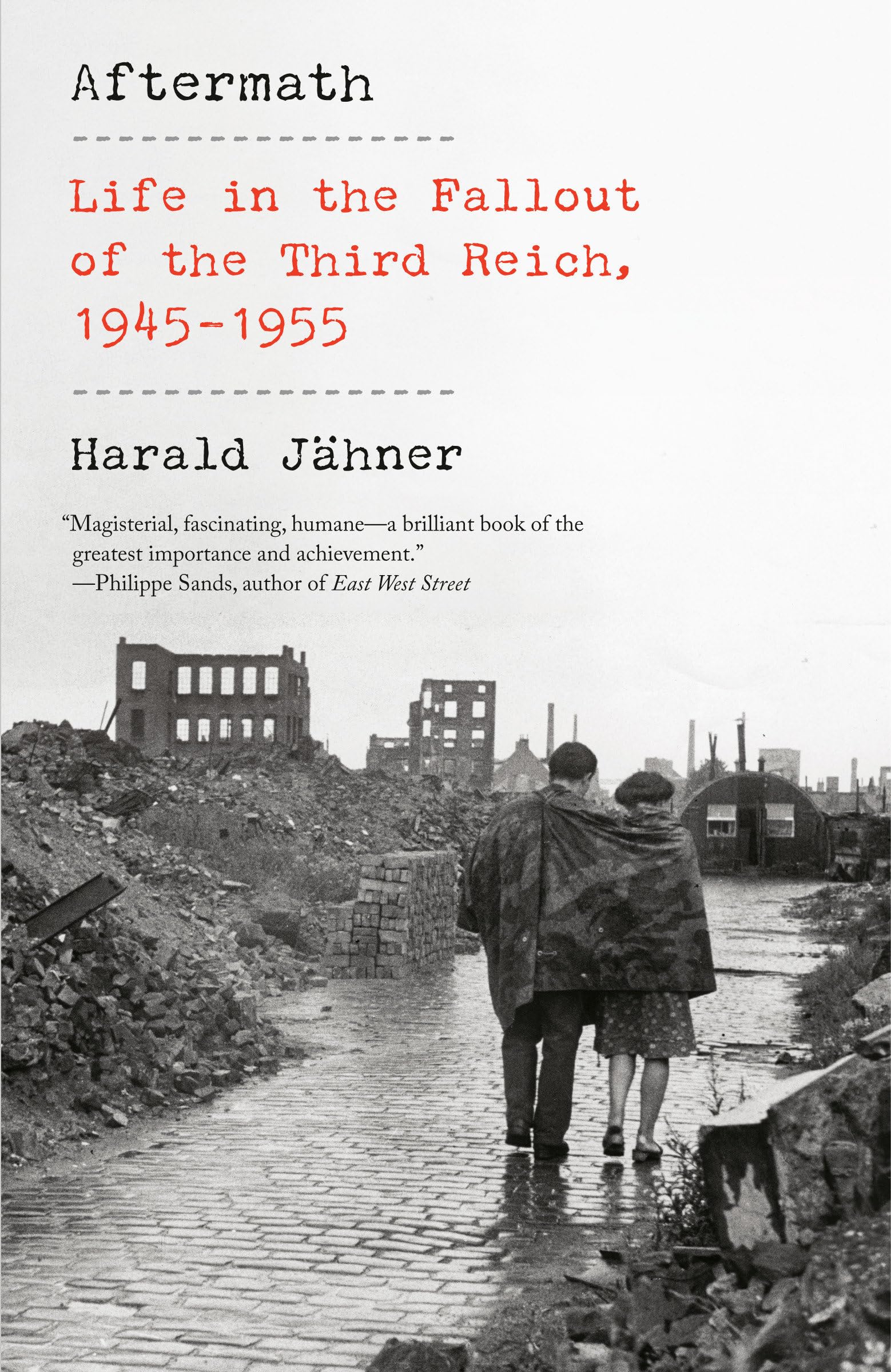

A Fascist Country Can Revive Itself, But It Won’t Be Pretty

“Aftermath: Life in the Fallout of the Third Reich, 1945-1955” by Harald Jähner is one of the greatest books of our time. It shows how an utmost destruction of a country that perpetrated unspeakable crimes does not preclude it and its people from a spectacular revival. But there won’t be a happy ending, only limited justice will be served, and there will be no atonement for a generation.In 1945, more than half of Germany’s population were refugees. The country lay in ruins. Germans chose self-victimization and honestly believed they were collectively victims of the war and not its perpetrators or enablers. This allowed them to rise again.In contrast with the rest of Europe, the Germans were well-fed until the very end of the war. Hunger, homelessness and poverty changed them in many ways. People struggled to come to terms with the necessity to steal to supplement their meager rations, which is a sheer absurdity if you think about the fact that they didn’t protest the forced disappearance of half a million of their own fellow citizens or any other Nazi crimes for that matter. Any mention of the Holocaust would draw a blank or cause lamentations about their own hardship. Allies tried to forcibly feed them the horrors of Auschwitz, but people would look the other way even if forced to sit in a movie theater where a movie about the concentration camps was shown. The practice was quickly acknowledged to be futile and impractical. Charlie Chaplin’s “Gold Rush” would cause a sensation, but his “Great Dictator” was withheld from Germans for many years because the original joke was deemed to be too fresh on them. The allies discarded the last vestiges of trying to be harsh with the population when the Cold War demanded cooptation of Germans into the two feuding political camps.Jähner shows how people came to terms with a total destruction of their world and found a new solace and joy in the sheer feeling of being alive. The girls of Berlin, many of whom were raped by Soviet soldiers, flocked into the movie theaters and dance polls after their daytime customary penance in for of cleaning the rubble, reserved as punishment for former members of the League of German Maidens. Cafes and bars were open almost on day one, usually among ruins. The Soviet administration in particular made sure that all the theaters and music halls were open immediately after Germany’s surrender (Russian officers loved culture, you see). People would find comfort in talking about culture, reinforcing their self-image as a peace-loving and refined nation which was somehow forced by the Nazis to commit the atrocities of the war. This narrative served the allies well - remember, they needed to co-opt Germans, so the absurd notion of Germans as sheer victims of the Nazis held for decades. It was not until well into the 1960s when the national penance started to manifest itself with the Auschwitz trials and the full exposure of the Holocaust. Until then the issue was mostly consigned to oblivion, and even the brightest intellectuals would be genuinely perplexed why Germany was frowned upon by other nations and used as a “whipping boy”. They shrugged off the German immigrants who came on the heels of the foreign victors to re-educate them. They were totally self-absolving about everything that Nazi Germany had done. “Life goes on because human consciousness is lifeless”, said Hans Habe, who tried to re-educate Germans in the 1940s using American money (and married three of the world’s most wealthy heiresses in the process).But even with no repent the German people were able to reinvent themselves. They worked tirelessly. They used a unique mixture of dodgeness and humor to overcome hardships. Qualified workers-refugees from Eastern Europe, initially greeted as “gypsies” by their fellow Germans in Germany proper, were able to revive manufacturing. They enjoyed new styles in architecture and furniture, and also modern art which was for some reason actively promoted and financed by the CIA. They built a genuine democracy in the Federal Republic - if at the cost of accepting about 6 million of former and mostly unrepentant Nazis in the process. Their good fortune was totally undeserved, according to Jähner. The true realization of the Nazi crimes would only come with later generations, which had a privilege of being born late, as Helmut Kohl sardonically pointed out.Jähner also speaks eloquently and powerfully about the changing fortunes of the German families. Immediately after the war, the women took upon their shoulders the burden of feeding their families. They were forced to drive lorries and tractors, and to send their children to stealing expeditions in a calculated hope that they wouldn’t be arrested because jails were already full with more serious offenders. Women took up all sorts of civil jobs only to find their fortunes diminish again when their emaciated, highly traumatized husbands returned home. Ugly blaming would flare up. Husbands fell as low as blaming their wives for being raped by Russian soldiers; and wifes blamed the husbands for starting their male war and then losing it. Children who were trading in the black market would rebel against their newly found fathers. The generation of 1968 would fight against everything their devastated parents held dear - but was able to understand something about the national guilt in the process.Jähner’s book is a cautionary tale for every country that, inexplicably even for itself, slips into fascism. Yes, there will be atonement and better fortunes, but nothing will be pretty about it. A people will need decades to come into its senses. It is perhaps inevitable. Read this book. It will help you understand what’s next for us in our own history.

J**F

Interesting Analysis of a Vanquished Enemy’s Rise

Jahner covers in meticulous detail how Germany arose from the ashes of WWII defeat to become a democratic and economic powerhouse in less than a generation. The theme of the book is that rather than feeling guilt for having murdered most of Europe’s Jews and perpetrated untold death on the world through Hitler’s war, the German postwar public considered themselves victims of circumstance. This is the story of how every aspect of German society coped with defeat.

A**R

Important consideration of what followed and what could follow any fascist

The idea of building new governance out of tyranny is very interesting. The idea that one government was split into capitalism and communism and that both of these governments had to address (or not address) the horrors perpetrated by the nation is compelling. I wish that the book would have addressed what the aftermath is post reunification. Is there a common sense of guilt or responsibility for the nation going forward? Should there be? And if so, how will they go about achieving that. Particularly of interest with the current emigre situation in Europe.

R**M

Interesting But Flawed Look at Post War Germany

As an American who lived in West Germany in 1960-64, I had high hopes for this book, to understand better the bizarre (at least to me) attitudes I encountered from Germans then about WW 2. On the plus side, the author gives readers a down to earth view of daily life for the average German in the years 1945-55, including cleaning up the "Rubble" of ruined cities, surviving the shortages of food (and just about everything else), and coping with the mass movements of refugees. However, the really important issues about how Germans confronted the truth about the unique and monumental horrors the Nazis brought upon the world are addressed in a subtle and unsatisfying manner. The author eventually reveals his theory that Germans recovered and built a functioning democracy only by engaging in a collective combination of amnesia and amnesty among themselves, taking on the role of "victims" of the Third Reich. As we know now from more recent historical analyses, many Germans fully supported and benefited from Hitler's monstrous schemes, but this fact is only briefly acknowledged by the author. In addition, the role of the Allied occupation in preventing a resurgence by the Nazis is minimized in this book. The author perhaps understandably wants to focus on the the resiliency of the German people, but I was expecting a more profound discussion of the character of the German people. This subject seems to be covered only in reference to a few quotes from the German-American philosopher Hannah Arendt, who visited Germany after the war. Overall, I found this book to be worthwhile, yet incomplete.

J**S

Excellent treatment of under reported time.

Hundreds of volumes have been written about the Second World War, with more on the way. Hundreds more are devoted to the Cold War that followed it. But what about life in Europe in the years following VE Day? We get glimpses here and there and some resources on the internet, but there are few studies in print.Harald Jãhner fills this void in this well-researched, yet readable book. Jãhner avoids the dry, fact-by-fact approach, telling the story from the perspective of those who lived it. He uses quotes from articles, interviews, biographies, and diaries; cites speeches and poetry, takes us into cinemas and dance halls.Though Jãhner is a German journalist, he takes an even-handed approach, looking dispassionately at how post-war Germans dealt (or did not deal) with guilt. He shows the often callous manner with which the Allies dealt with German suffering, while acknowledging the formidable task of feeding and housing the post-war population they inherited. He documents the resentment rural Germans felt toward their displaced urban "immigrants," the tensions when different German cultures were forced to live side-by-side, and even the cold reaction of surviving secular German Jews to the deeply religious DPs from Eastern Europe.This book is a must for anyone trying to understand the war in Europe and its aftermath.

T**A

finding a future despite a past built on destruction

It’s almost impossible to sum up this book.The critical question was how a democracy managed to emerge from a past of repression and fascism - how did modern Germany reconcile itself with its Nazi past? And the answer seems to be - there was no reconciliation. The past was ignored and dismissed for many, former members of the Nazi Party and SS carried on with their pre-war careers and collected their pensions. The Nuremberg Trials of the 1940s were similarly ignored. The rationale for the German public seemed to be: it doesn’t matter where you came from it matters where you’re going. And most Germans wanted to head towards a future that left their Nazi past with all its attendant guilt, far behind. They wanted to remake themselves and their future. It was only their children who, in the 1960s, as buried truths emerged about the death camps, hurled furious accusations at their parents and grandparents and demanded an accounting.I wonder what my German side felt? They were in Magdeburg but once the wall went up they were silenced. When the wall came down they could no longer be located. So all I ever knew about them was old postcards in German that had been collected in the late 40s and 50s.An extraordinary book, very readable, and well worth your time in coming to an understanding of modern Germany as well as the modern Europe of which it is such a strong and crucial element.

B**L

the best book about the wwii I’ve ever read

Superbly written and amazingly cited. Full of interesting facts about life in post war Germany. Definitely recommend it to anyone who’s interested in the topics!

I**S

Empathy for the displaced

A great read for those able to empathise with the fate of so many millions of people - non-German as well as German - who were displaced after the end of WW2 and found themselves in Germany: 75 million, of which 40 million were homeless or in camps (temporary camps and others more permanent), of which there were 10 million German soldiers being processed by the Allies, left in the open, without latrines or shelter, under armed guard, in the meadows along the Rhine. An extraordinary sight, if you can inagine it.The author is careful to attribute his sources, which adds to the credibility of this account of post-war Germany’s fate. This account is such a poignant warning to those intent on military aggression in the future.Considering all that he might have discussed, the book is too short (382pp). There is so much more that he might have discussed in greater detail; for instance, the practical and psychological consequences for the 2 million women who were raped after Germany’s defeat.This book is a testimony to the horrors of war and why political leaders who advocate aggression ought to be cut down at the knees immediately by their respective countrymen and women. Do not allow yourself to be tempted by an appeal to national exceptionalism and arrogance. 🇺🇦/🇷🇺My only criticism is quite specific, but perhaps there were financial reasons for this (publishers do themselves no favours when they skimp): when the author discusses landscapes, imagery, photography, creative individuals processing the consequences of Germany’s defeat and their country’s total and utter defeat, more examples could have been shown and reproduced - but importantly placed closer in the text at the point where they are first discussed.

B**M

Extremely disappointed with the book. Falls way short of expectations.

Just to give some context - I am a complete World War 2 nerd and have a cupboard full of books on WW2. For months I had been wanting to read about what happened immediately after the end of WW2 - after the capitulation of Nazi Germany in 1945. This book sounded very promising. However, when I started it and went through the first few chapters I was appalled. First of all, the author is not a serious historian, and should not be considered as such. Too often he lets his own opinions and beliefs get mixed with the facts from his research. He makes sweeping statements like "Most Germans made their acquaintance with hunger only after the war. Until then they had lived reasonably well by plundering the occupied territories". As if the people lived heartily in full stomachs amidst the bombed-out buildings and the rubble! More egregious is his comment that the rapes of the German women by Russian soldiers at the end of the war could be justified, in part, because of the heinous crimes committed by the Nazis on the Soviet population. We are talking about what probably was the most systematic and violent campaign of raping ever perpetrated by a group of men in history, and for this author it was just a case of tit-for-tat! Reading that chapter made me sick to my stomach. Basically, the author fills the whole book with the "Allies were good, Germans were evil" sentiment. Felt like I was reading from an 8th grader's history project. However, the saving grace to some extent are the interesting facts one can find here. Such as the British and Americans rationing the local population in the occupied zones to 1,550 calories daily - which represented only 65% of what doctors at the time considered necessary for the nutrition of the average adult. A deliberate strategy of starving the Germans and making sure a whole generation would grow up malnourished and weak - bet you wouldn't know that from any history book or movie where the brave American or English soldier fights the evil Germans!

L**N

A Must read

This book is very text bookish and has lots of good info that I never received in school in the 70‘s! Gives you a better understanding of the afterlife and present day German thinking. A helpful for me as an expat American lining in Bavaria. It has opened dialogue as well with my Deutsch friends. Highly recommend!

Trustpilot

3 days ago

2 weeks ago