Customer Services

Copyright © 2025 Desertcart Holdings Limited

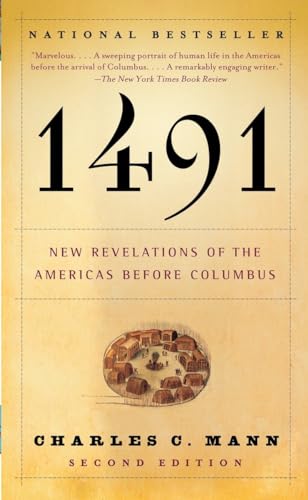

desertcart.com: 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus: 9781400032051: Mann, Charles C.: Books Review: Great stories, great research, and a good treatment of the topic - I'll be the first to admit that my interests in the historical have generally been Eurocentric, especially the Roman Republic and Empire. Recently, though, I found reason to pick up Charles C. Mann's "1491," and I have had a hard time putting it down since. The children's nursery rhyme reminds us that "In 1492, Columbus sailed the ocean blue." Just this last week we've celebrated Thanksgiving and the mythologized first meal shared by "Pilgrims" and Native Americans in the early years of Captain John Smith's Plymouth Colony in the 1620s. But what came before Europeans in the "New World" of North and South America? What was already here when they arrived? Was there much more than a few human sacrificing Aztecs (in South and Central America) and nomadic tribes in North America? Quite the contrary, says Mann. Rather, he says, the land was full of people, developed into complex cultures and polities. For example, and he expands on many, the Maya controlled an empire that was larger than any in the old world, both in size and population. The Mexica (pronounced Meh-shi-ka) had a literary culture full of metaphor and simile, and a rhetorical tradition that enabled them to meet Franciscan friars sent to convert them on equal ground. In North America, as far as the shores of New England, the coast was full hundreds of thousands of Native Americans-the nations of the Micmac, Passamoquoddy, Abenaki, Mahican, and the Massachusett, among others. Indeed, there were so many people in both North and South America that Mann wonders if settlement by European colonists would have been possible but for the effects of disease on the native population. So devastating were diseases such as small pox, influenza, and non-sexually transmitted hepatitis that civilizations such as the Maya may have been destroyed before Europeans even landed on the shores of South America. Similarly, the nations of New England, which had filled the land and had traded with early French and English merchants during the 16th century, almost disappeared over a period as short as two to five years. Why was disease so devastating? While not the central focus of the book, or even the examination of "what was here before 1492," Mann explains how the relatively limited genetic stock of Native Americans presented insufficient diversity for the native populations to survive the diseases that had been active in Europe and Africa for thousands of years. Native Americans were in no way inferior-they just came from fewer people and thus had less genetic diversity, had never faced diseases as the Europeans (and their pigs) carried and therefore fewer of them survived the introduction of the diseases to the American peoples. The result was that within a few years, entire nations and their cultures all but vanished from the Earth...leaving the appearance of a empty land with only a few roving tribes. Indeed, says Mann, the reason those tribes were roving may be because they had been cut down from populations levels necessary to support a stable and stationary settlement. Among some of the other interesting tales and studies that Mann shares in his book is the story of Tisquantum, who we know as Squanto. His name, which he may have given himself, meant something along the lines of "wrath of God," and Mann suggests that when he appeared in the Plymouth Colony, his intentions may not have been as benign as have been told to us in elementary school pageants. Born an original New Englander, he was kidnapped by Europeans as a souvenir and taken to Spain. Eventually, he ended up in England in the home of a rich merchant, again as an oddity to show to visitors. Learning English, he eventually convinced the merchant to send him back to America. However, in the time between his kidnapping and return, hepatitis ran rampant through his and the other nations living in what is not modern-day Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Maine, wiping out his people and others. He returned to an empty land and was captured by a rival nation, who later used him and his ability to speak English to liaison with the Plymouth Colony. He, in return, may have tried to use the colonists as leverage to take over the rival nation. 1491 is a fascinating book, and a fascinating piece of history, covering a period of history that we may have spent less time examining than is merited given the size and scope of the civilizations that preceded European colonization of the Americas. Containing cities that dwarfed Rome in its greatest day and Paris and London at the time, the Americas in 1491 were, by Mann's telling, a busy, populated and colorful place, and it deserves a place in our histories and archives alongside those of the other great civilizations of history. Review: Great book, so much incredible history - Great book! Fascinating recent discoveries about the Americas!! And well written.

| Best Sellers Rank | #6,722 in Books ( See Top 100 in Books ) #3 in Indigenous History #11 in Native American History (Books) #43 in Sociology Reference |

| Customer Reviews | 4.6 4.6 out of 5 stars (6,664) |

| Dimensions | 5.1 x 1.1 x 7.9 inches |

| Edition | First Edition |

| ISBN-10 | 1400032059 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1400032051 |

| Item Weight | 2.31 pounds |

| Language | English |

| Print length | 541 pages |

| Publication date | October 10, 2006 |

| Publisher | Vintage |

D**N

Great stories, great research, and a good treatment of the topic

I'll be the first to admit that my interests in the historical have generally been Eurocentric, especially the Roman Republic and Empire. Recently, though, I found reason to pick up Charles C. Mann's "1491," and I have had a hard time putting it down since. The children's nursery rhyme reminds us that "In 1492, Columbus sailed the ocean blue." Just this last week we've celebrated Thanksgiving and the mythologized first meal shared by "Pilgrims" and Native Americans in the early years of Captain John Smith's Plymouth Colony in the 1620s. But what came before Europeans in the "New World" of North and South America? What was already here when they arrived? Was there much more than a few human sacrificing Aztecs (in South and Central America) and nomadic tribes in North America? Quite the contrary, says Mann. Rather, he says, the land was full of people, developed into complex cultures and polities. For example, and he expands on many, the Maya controlled an empire that was larger than any in the old world, both in size and population. The Mexica (pronounced Meh-shi-ka) had a literary culture full of metaphor and simile, and a rhetorical tradition that enabled them to meet Franciscan friars sent to convert them on equal ground. In North America, as far as the shores of New England, the coast was full hundreds of thousands of Native Americans-the nations of the Micmac, Passamoquoddy, Abenaki, Mahican, and the Massachusett, among others. Indeed, there were so many people in both North and South America that Mann wonders if settlement by European colonists would have been possible but for the effects of disease on the native population. So devastating were diseases such as small pox, influenza, and non-sexually transmitted hepatitis that civilizations such as the Maya may have been destroyed before Europeans even landed on the shores of South America. Similarly, the nations of New England, which had filled the land and had traded with early French and English merchants during the 16th century, almost disappeared over a period as short as two to five years. Why was disease so devastating? While not the central focus of the book, or even the examination of "what was here before 1492," Mann explains how the relatively limited genetic stock of Native Americans presented insufficient diversity for the native populations to survive the diseases that had been active in Europe and Africa for thousands of years. Native Americans were in no way inferior-they just came from fewer people and thus had less genetic diversity, had never faced diseases as the Europeans (and their pigs) carried and therefore fewer of them survived the introduction of the diseases to the American peoples. The result was that within a few years, entire nations and their cultures all but vanished from the Earth...leaving the appearance of a empty land with only a few roving tribes. Indeed, says Mann, the reason those tribes were roving may be because they had been cut down from populations levels necessary to support a stable and stationary settlement. Among some of the other interesting tales and studies that Mann shares in his book is the story of Tisquantum, who we know as Squanto. His name, which he may have given himself, meant something along the lines of "wrath of God," and Mann suggests that when he appeared in the Plymouth Colony, his intentions may not have been as benign as have been told to us in elementary school pageants. Born an original New Englander, he was kidnapped by Europeans as a souvenir and taken to Spain. Eventually, he ended up in England in the home of a rich merchant, again as an oddity to show to visitors. Learning English, he eventually convinced the merchant to send him back to America. However, in the time between his kidnapping and return, hepatitis ran rampant through his and the other nations living in what is not modern-day Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Maine, wiping out his people and others. He returned to an empty land and was captured by a rival nation, who later used him and his ability to speak English to liaison with the Plymouth Colony. He, in return, may have tried to use the colonists as leverage to take over the rival nation. 1491 is a fascinating book, and a fascinating piece of history, covering a period of history that we may have spent less time examining than is merited given the size and scope of the civilizations that preceded European colonization of the Americas. Containing cities that dwarfed Rome in its greatest day and Paris and London at the time, the Americas in 1491 were, by Mann's telling, a busy, populated and colorful place, and it deserves a place in our histories and archives alongside those of the other great civilizations of history.

B**A

Great book, so much incredible history

Great book! Fascinating recent discoveries about the Americas!! And well written.

W**.

An eyeopener about Pre-Columbus American Indians!

Charles C. Mann’s book, 1491, provides us with an eye opener about the pre-Columbus populations of the North and South America. It is not an easy read: it is very detailed and well researched with references to critical scientific studies. It is not a chronological or systematic account, and this makes the book somewhat disjointed. Mann’s main intents were to examine Indian demography, Indian origins and Indian ecology. In my opinion, he is not successful in the first objective of describing Indian demography. However, I doubt there are enough research available to tackle this objective. They may never be enough research as there were multiple occupations of land by unknown populations throughout the period from the first arrivals of the peoples loosely described as Indians to the present day. Also, the populations were dynamic, growing and shrinking depending on the social and natural environments of various groups of Indians. The task may just be too difficult to build a record of Indian populations prior to the arrival of Christopher Columbus. Mann has tried to report the research faithfully but the Indian populations of Western United States and that of Argentina in my opinion, not well researched, and thus understated in this book. It is also possible that populations reported are also understated. Mann has been more successful in the second two objectives and particularly the third. I think the overriding theme of this book is that pre-Columbian inhabitants of the Americas shaped their environment to fit their needs, no more than we do today and certainly, no less. Where we think that that current forests are wild and untouched by man, in fact, they are the results of previous inhabitation of the lands. There is no more a representation of this than the forests in the vicinity of the Amazon River. However, after the demise of the inhabiting culture, what remains is an overgrowth of plant and animal life. And this is true in North and Central America as well! It can be said definitively based on research that the Indian populations did not live lightly on the land. I found the book at the first reading contradictory of what I had been taught of American Indians after growing up in Montana and having lived with Yupik Eskimos (technically, Eskimos are not Indians,) in Western Alaska. In the first Chapter, Mann indicates that I would have this experience. But I find the research he quotes valid and confirmatory of his arguments. In addition, he often provides alternative arguments. Mann is not the author of this research, but the reporter of the research. Before reading and finishing the book, I did not read reviews of it. Thus, as I read it, I was amazed at the information and oftentimes, skeptical. However, I read several of the research reports referenced. Then, on finishing the book, I read several reviews both positive and critical. The book is widely acclaimed. The critical reviews stem mainly from people who found the book too detailed for their tastes and too difficult to read. One of the critical reviews was from an interpreter of the Cahokia site in Illinois who questions Mann’s statements which originated from Professor Woods. However, this same interpreter does not provide alternative research to support his claims. There probably is nothing more understood in the United States, and perhaps the World, than the pre-Columbus North and South American cultures. There are many reasons for this. First and foremost, Columbus in his search for Asia did not know the Americas nor had he ever been to the coastlines of Asia. Therefore, on reaching America, he thought he had reached Asia and thought the peoples he witnessed where of India. Thus, he named them “Indians” and the name, despite the confusion, has remained to this day and is a global term for all of the pre-Columbus inhabitants even though there are major distinctions in their cultures and genetics. While a number of the various tribes and nations object to the use of the word “Indian,” no better term has emerged that all will accept. For a discussion of this, see Appendix A of 1491. Second, most of the pre-Columbus inhabitants of the Americas either did not have writing or not a form of writing recognized by the European explorers and invaders. The result was that much of the written information of the pre-Columbus inhabitants had been lost either through decay of whatever records there were or through the willful destruction of the records by the invaders. Where there were no known records, Europeans interested in pre-Columbus cultures had to rely on the inhabitants themselves who were often recent transplants to the regions. Third, the pre-Columbus population of the Americas has been estimated from the finds of various archeological sites to be as high as 125 million people. Yet when early European scholars arrived to study and record Indian cultures, they found only remnants of the populations. It is accepted that European diseases such as small pox, influenza, and others, killed the vast majority of the populations that existed and that this happened in a very short time after the arrival of the first Europeans. For example, De Soto records thousands of people living in current day Arkansas. When La Salle visited this area a century later, he could find almost no traces of man. The estimates that Charles Mann seems to believe that the population loss was 95%! While this is arguable, it is also creditable based on eye witness accounts of the effects of small pox on various indigenous peoples. Thus, many Europeans recorded for history the shell-shocked left overs of populations essentially no longer functional. For these reasons, the attempt to build a history of pre-Columbus cultures will be problematic. Also, the popular cultures we have today in the United States have built up fantasies around the Indian cultures which are also promulgated in our school systems. These have influenced past researchers trying to understand Indian cultures. And they made, now known, mistakes in their assumptions and conclusions. As Mann clearly shows, the research today using more modern techniques is building a much different picture. The archeology of the Americas shows that we need to question almost everything that we have been taught. It is taught that the Indians cross the land bridge at Beringia during the last ice age (13,000 years ago,) and then descended South using a narrow strip of land near the current Continental Divide which did not ice over some 12, 000 years ago. Then it would take another 1000 years to enter and populate South America. Yet, the evidence suggests something different also happened. The ice-free path proposed has yet to yield artifacts that would support such a theory. It is possible that perhaps the path was the Western seaboard of North America, though. The genetics of certain Indians in Amazonia are distinct from those of North America. An archaeological dig in Southern Chiles found human artifacts that predated the supposed Beringia crossing. There is evidence of culture at Painted Rock Cave near Santarem on the Amazon River that is contemporary with the Clovis culture which is the earliest found in North America. Thus, while Beringia may be part of the story, it not all of the story on how the Americas were populated. More research is still needed here. Another major point assumed was that the Indian cultures did not have the sophistication of European cultures in pre-Columbus societies. Research finds that the Olmec, who were inhabitants of Mexico approximately 1800 B.C., were using the number zero in its mathematical form well before it was invented in India a few centuries A.D. They created a 365-day calendar more accurate than the calendars in use in Europe. In addition, they were recording the Olmec history on folded books of bark paper, now called codices. Many of these were destroyed by the Spanish when they were found, so only a few remain extant. It can be said their cultures were different than those of the European but no less complex. Overall, this book while not easy to read, if a very worthwhile read. I feel this is a work in progress: new research will emerge on the Indian populations of the Americas. Mann has provided a current state of the art understanding of Indian cultures in the Americas based on known and referenced research. It is clear that what schools are teaching about Indian populations needs to change and acknowledge the results of this research.

M**P

Muy buen libro y el paquete llegó en tiempo y buenas condiciones

A**R

Well researched, insightful at all times

G**Y

Very interesting history of Native Americans and Inka Empire.

P**Z

what was expected

J**X

An engaging and culturally rich book which displays a rich range of knowledge and many years’ study. I came to this book after reading one of Mann’s articles in National Geographic where I was struck by the sensitivity and grasp he had of the topic (not always a luxury in journalistic coverage but something many feature writers would ideally like to achieve). The book challenges conventional nationalistic history using an evidence-based approach, rather than polemic, and with an engaging humorous and anecdotal structure. The book is rightly (gently) critical of the way that the topic has been dealt with from an imperialist academic perspective and highlighting the often obfuscated role of the ordinary people who came across archaeological sites. At the same time it pulls no punches when discussing the politicisation of Mesoamerican histories, whether imperialist apology or native activism. A series of endnotes and bibliographic sources opens the door to further enquiry.

Trustpilot

2 weeks ago

2 weeks ago